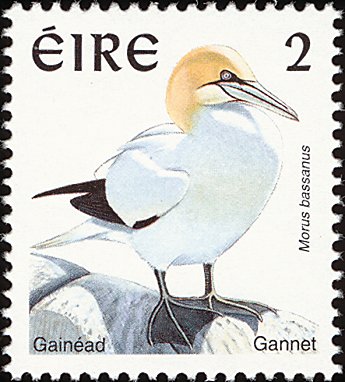

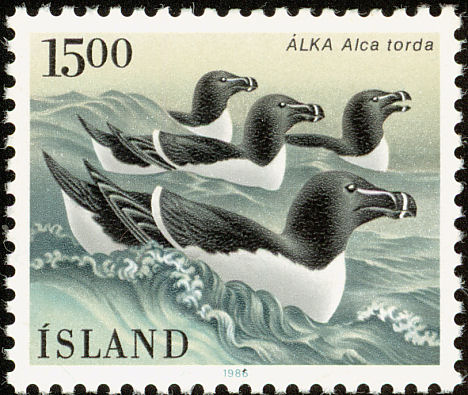

| Bird | Number | |

| Gannet - More | 3 pairs | |

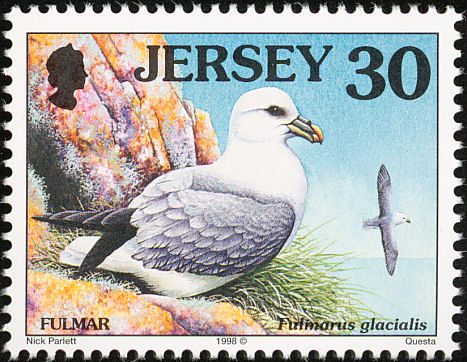

| Fulmar | 4,029 pairs | |

| Puffin | 48 pairs | |

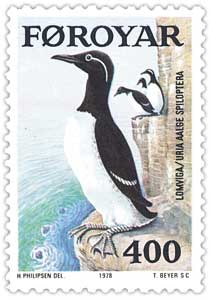

| Guillemot | 1,528 pairs | |

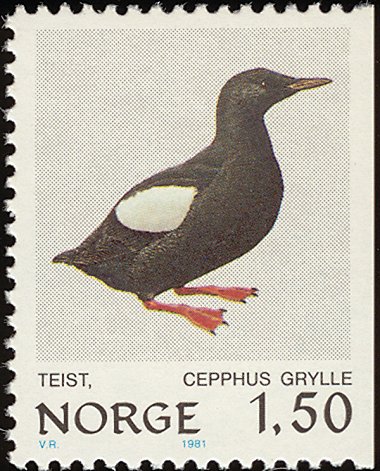

| Black Guillemot | 62 individuals | |

| Razorbill | 354 pairs | |

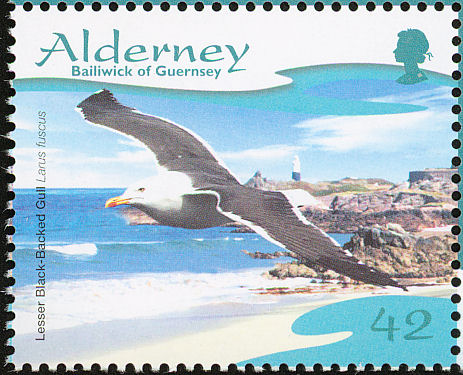

| Lesser Black-backed Gull | 14 pairs | |

| Great Black-backed Gull | 24 pairs | |

| Kittiwake | 1,785 pairs | |

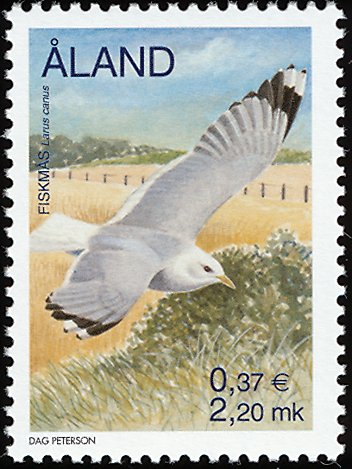

| Common Gull | 39 pairs | |

| Shag | 89 pairs | |

| Chough | 16 pairs | |

| Figures per NPWS website. These numbers indicate the presence of and population size of breeding birds. | ||

April's first lambs shine out on the hillside, their whiter-than-whiteness rhymed in the breakers unfurl'ng at the shore. Celandines, primroses, dandelions gleam below the:greening hawthorn hedges. A crowd, .a host of golden dung-flies dip for nectar at an early cow-parsley. To be out sowing potatoes on such a day, attended by warbling robins and tumbling ravens is to have a privileged occupation.

It grows ever more so, here at the last frontier of change. A couple of decades ago, I would take out my spade in the comfortable knowledge that half-a-dozen neighbours, spread along the hillside, were using a pet day in much the same way. Getting the spuds in, getting them moulded, spraying the stalks against the blighty drizzles of summer, lifting the crop in autumn - these rituals counted out the seasons.

Today, the early-morning cars zoom over the hill to Westport and Castlebar where the sky's the hmit for every kind of construction skill. And in the hard-pressed world of part-time farming, growing and protecting a whole years potatoes can be just one complication too many.

The new lambs dance on grassed-over potato ridges frozen in form since the Famine. 'The hillside above the road is quilted with them: a corduroy patchwork running this way and that, sharp-etched by the sun as it rises over the ridge . Climbing up beside the stream - leaping, in places, from one ridge to the next in an awkward, bounding progress - I come to flat boulders bearing little heaps of stones. They are fixed in a matrix of moss and.lichens. 1 touch. them, to hear the shouts of children on this crowded hillside, smell the turf-smoke from cabins hunched In a wasteland of black soil.

Frank Mitchell once read this landscape with me, tracing out its palimpsest of human uses. Remnants of Neolithic walls trail up between the Land Commission fences; an ancient cattle-pen perches: beneath the ridge; the burnt stones of a Bronze Age fulacht fiadh mark the bend of a vanished stream. Earthen ripples of lazy-beds: flow over and around the marks of centunes, between the Stone Age farmers and the metal spade.

The hillside looks west to Clare Island, where corrugations of ridges still cover much of the arable land with a stubborn permanence. In Brian Lynch's image."the island has been pleated like a piece of paper that cannot be smoothed out''. He wrote this in Easter Snow (1993), in which Peter Jankowsky's camera saw the ridges as earth-breasts, as passage graves, as waves of an ocean washing over to fields. I have felt that somewhere on Clare was the perfect site for John Behan's magnificent Famine ship, now stranded -- movingly enough -- at the foot of Croagh Patrick opposite.

Clare Island's lazy beds are, indeed, special, surviving even the overgrazing that has threatened to strip parts of its great hill to the bare rock. In the first volume of the New Survey of Clare Island Críostóir Mac Cárthaigh calls them " a very pronounced version" of the usual Irish spade-ridge. Where soil is good and drainage reasonable, a ridge may be as little as one metre across. But on Clare they become earthworks as much as three metres wide and separated by knee high trenches to carry the rain away.

As one who, for many years, fashioned four-foot-wide ridges with the long handled west Mayo spade, I take a practitioner's interest in the accounts of their ecological refinement -- tilting their surface, for example, to cheat the wind and caatch the sun, or curving them on sloping ground on order to check the soil-creep of erosion.

On my warm and well-drained acre I have now succumbed to convenience and sow potatoes on the flat, under a mulch of woven black plastic that lets the rain through (but not the weeds). I know this must be progress but sense another ending. Hay-making, cutting turf with a slean, sowing potatoes in lazy-beds (or at all) . . . we're in 2000 now.

On Clare Island, says Mac Cárthaigh, "wide spade ridges are still preferred for potato growing'' and black sea wrack as fertiliser is still used to a limited extent''. And there are just two surviving Clare Island-built currachs, one of them beached for the present. The plan of the other one makes a typically handsome page in the new RIA publication.

This first volume from the re-survey of the island - "History and Cultural Landscape'' - may not be what many people would have expected from an enterprise that is, first of all, scientific. But this is tp forget that the original survey, master-minded by Robert Lloyd Praeger over the three years 1909-11, studied the island's folklore, landscape and place-names quite as assiduously as it did its flora and fauna.

The first book. therefore, sets the scene, in chapters every bit as readable and well-illustrated as, say, the recent Atlas of the Irish Rural Landscape. Timothy Collins describes the original survey, which was in many ways the grand climax in Ireland of the Victorian era of naturalists' field clubs. The amateurs worked alongside more than 100 scientists recruited from Europe as well as Ireland, finding and putting a name to every plant that grew, every creature that moved on or around the island. Their reports comprised an ultimate baseline inventory on a scale rarely attempted anywhere in the world.

What should be fascinating in the volumes still to come, is to see what has changed in almost a century and - even more importantly - to be given ecological insight into understanding why it has happened.

Meanwhile in Book One, Críostóir Mac Cárthaigh's review of Clare's folklife (houses, fishing, farming) is grouped with Kevm Whelan's perspective of the island's landscape and society in the two centuries to 1900, and Nollaig Ó Muráile has whole pages of place-nnmes that weren't recorded in1911.

This is certainly a book to enrich one's understanding of the history, both of Clare Island and of the Connasht coast in general. I do find it disconcerting, however, that "folklife'' seems to deal almost exclusively in continuities with the past: you will learn very little from this volume about the common life of Clare Island today.

New Survey of Clare Island is published by Royal Irlsh Academy, price £20