Duvillaun More

Dubhoileán Mór (Blackisland Great)

Within the Mullet - Rita Nolan - 1998

The birds of Duvillaun More Island ,

Wikipedia

NPWS

Another Life

Michael Vineyin the Irish Times - October 1988

The wind above the cliffs was dishevelling even for a peregrine. It tugged so fiercely at the thatch of his wings that the usual trim anchor of their silhouette was split into a fistful of dark knives. The falcon hung perhaps 30 feet up from the cliff and 100 from the seething sea below and screamed at me angrily for half an hour.

I had entered his territory at the western end of Duvillaun Mor , where the smooth whaleback of the island is fractured into isolated stacks. Each separated tower is topped with grass and sea-pink cushions - a draping prettily at odds with the sheer and brutal planes of rock below, sweating -wlth spray and echoing like dungeons.

Safe on the island's main substance, I lay on my back among the pillowing thrift , and ogled the falcon through binoculars. He had a reglar station in the air, poised centre stage, above an amphitheatre of cliffs, and returned to it again and again to hover and point into the wind like a windvane or a compass-needle. His busybody circlngs led insistent, imperious screaming became slightly ridiculous.

It seemed such a lonely and pointless vigil. With the cliff edges now deserted by their summer throng of nesting fulmars and kittiwakes, the falcon's breeding territory was comparatively empty of prey. True, the mattress of sea pinks held scores of rabbits - among them, the black-furred strain of which I wrote last week - but these are not the natural quarry of a peregrine:

For a choice of birds beyond Duvillaun's rock pipits and gulls, the falcon would have to travel. The sandy coves of Inishkea and the long strands of the Mullet, each of them a mere three or four miles away, were now teeming with waders arriving daily from the north. On Inishkea I had watched flocks of tiny sanderling, sifting down like snowflakes to begin a frantic, ravenous feeding at the edge of the tide. They joined turnstones and oystercatchers, purple sandpipers, bar-tailed godwit - all birds that had nothing to hope for from the cliff-bound shores of Duvillaun.

Yet this island had its own, unexpected, comings apd goings. There were passing windfalls of Arctic snowbuntmgs, and their early arrival was an odd counterpoint to the sound that reached me on my first night, as I lay awake in a gale. Beyond the snappng tent wall and the snarling wind I heard something that belonged to memorable summer nights on Inishvlcklllane in the Blaskets or Ardilaun off Connemara or the Bills beyond Achill: the rhythmic purring and hiccupping of a storm petrel.

It must emanate, I knew, from the stone walls around the tent - ruins were sheltering it from the worst of the storm. The petrel will nest in almost any sort of dark crevice or empty rabbit hole, but it has made especially its own the drystone ruins and walls and beehive cells left behind by man's brief occupation of the remoter Atlantic islands.

The petrels are our smallest seabirds, fragile sparrows of the open ocean that most people have never seen. They flutter low over the waves, feet sometimes pattering the surface as they pick up food with their bills. They come ashore only to nest and then arnve and depart strictly by night, like bats. In June, I have had them strike my tent, as they returned from the sea at midnight to find it pitched in their flight-path.

But in fact, the storm petrels start landing in April and their eggs, one to each nest are laidd usually in the second half of June The hatching and fledging of the young bird is a long process. It is fed almost nightly for the first seven weeks, but the midnight meals (a regurgitated squirt of an oily, fishy substance) then become irregular, with gaps of up to five days. By the time it flies it may not have been fed for a week, and its departure to sea, at anything up to 73 days old may not take place until the first week in November.

I had no intention of disturbing a petrel nest, but when the gale continued (as it was to do, from varying directions, for the next five days) l got up at first light to add a foot or two to the wall behind my tent. As 1 hoisted the large rocks, whiskery with lichen, from the pile of a fallen gable, I suddenly glimpsed a substantial ball of fluff in a crevice I had uncovered. It was a petrel chick well on in fledging, its feathers growing out on the same shafts as the fluff. l replaced the rock carefully and left it in peace.

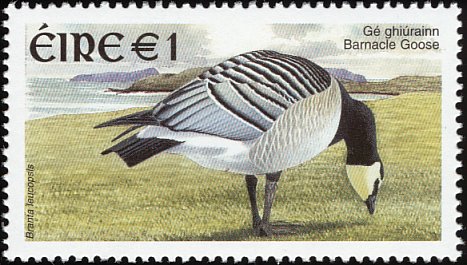

But of all the calls borne on the winds of Duvillaun, the one with a special resonance for David Cabot and me was the guttural flight-chatter of barnacle geese , the birds we have twice pursued to their breeding cliffs in Greenland. The little groups that circled : the island and roosted briefly at its boggy ponds were part of a great influx to the barnacles' main wintering-grounds on nearby Inishke.

When, at length, we had finished filming Duvillaun's grey seals

ContinuedPermission to reproduce from article - courtesy Michael Viney

Within the Mullet

Rita Nolandescribes life on Duvillaunmore in her book

Duvillaunmore and its satellites are the most southerly of the islands of the Mullet. While they lie much closer to the Mullet than to Achill their rock formation is similar to that of Achill. The major rock type there is quartzite, as it is in Achill while here on the Mullet and its other islands the main rock is gneiss. It is probable that Duvillaunmore, like Inishkea, was always inhabited, though there is no record of habitation from early christian times until the 19th century It has I 80 acres of good grazing land and a further 70 acres on Duvillaunbeg - albeit very exposed to wind and sea. Unlike the other islands Duvillaun has the advantage of having its own turf supply. The turf there burns with a blue light because of the presence of copper in the soil. 26 It was originally part of the Bingham Estate, though it later became the property of the Gambell family who owned land in Surge View and had a big lodge there.

About the middle of the nineteenth century the Brennan, Hogan, Earley, Corduff and Egan families lived on Duvillaun. The Earleys had first lived in Blacksod and later moved to the island. The Corduff brothers, Michael and Martin, had come from Rossport to Falmore. Michael remained in Falmore but Martin later moved to Duvillaun. In the 1860's they were joined by a Barrett family and the Mac Conaola family who made their way there by yawl, all the way from Connemara. They were probably lured by the good fishing, as were the Lavelles and O'Donnells to lnishkea. Due to an official error Mac Conaola was later mistranslated to McNeely. During the 1880's the Brennan and Hogan families took advantage of the Tuke emigration scheme and went to America. The Corduffs and Conneelys intermarried and had large families. Tom Conneely and Mary Corduff had nine children between 1865 and 1887. Martin Corduff and Mary Gavin had eight children between 1875 and 1895. The Barrett family had seven children between 1870 and 1892. 27 Dennis Egan and Anne Murphy had two children. There was a young and thriving population on Duvillaun and they had a good life on the island. Arthur Gambell was a kind landlord who did not oppress them. The Conneely family had brought their poitín making skills with them from Connemara. No doubt the Corduffs had talents in that field too, and they combined to make first class poitín - in stiff competition with Inishkea. The Duvillaun people claimed that they produced whiskey rather than poitín. They coloured it - originally with herbs, later probably with tea - and left it to mature for 3 to 5 years. They too did a brisk trade on the mainland - and were sometimes caught. In 1892 two Conneely brothers were on their way to deliver a consignment to Denis Bingham at the Castle when they were accosted by policemen. Frank Conneely was arrested but his brother Tom escaped, made his way to Port Mór in Glosh, and got a currach from there to Duvillaun. Mrs. Hynes of Belmullet paid Frank's fine, and gave him £5, with which he emigrated to America. Some years before, when she was still Miss Flynn, Mrs. Hynes had taught in lnishkea. The Duvillaun children attended school in Inishkea South - travelling there and back by currach - and staying with the McGinty family during the school week. So Mrs. Hynes would have known Frank. Not all of the Duvillaun children went to school. Duvillaun never had its own school and some of the children remained illiterate.

By then the good days on the island were coming to an end. Arthur Gambell was bankrupt, his lands were in Receivership and he was forced to flee the country. The new landlord was less sympathetic. She was Mrs. Agnes McDonnell of Tón a' tSean Bhaile in Achill, but known to the people of Duvillaun as "Cailleach a' Valley''. She made headlines shortly afterwards when Loinseachán, her bailiff, burned down her stables and attacked her with a pick-axe, leaving her for dead. She was saved by her servants. Before this event she had raised the rents in Duvillaun and had sent Loinseachán in a boat to collect them. The boatman, Martin Patterson - known as Máirtín a ' Bhobbaí - who was a friend of the islanders, broke the steering so that the boat could not land. Cailleach a' Valley was not to be defeated so easily. The next raid was much more serious, led by the policemen from Inishkea in their gun-boat, escorted by a posse from lnishkea North in a flotilla of yawls. They come at night, took the families in Duvillaun by surprise. and tied them to the gables of the houses, while they rounded up their animals and took them away in the boats. According to the people of Duvillaun they also broke furniture and did a great deal of damage to property. The islanders were forced to leave. In 1895 they came out of Duvillaun - the Earleys and Corduffs to Falmore and the Conneelys to Blacksod. Biddy Earley, the last survivor, died in Arus Deirbhle in 1992 - aged 98. Biddy was born in a currach between Duvillaun and Blacksod in 1894. 26 Duvillaun too has been left to the birds. It is not even enlivened by the shouts of occasional day-trippers.

The depopulation of our islands has been a God-send to a wide variety of birds. They have found a safe and peaceful haven on them. Duvillaunmore is a breeding ground for storm petrels, fulmars, shags. cormorants, choughs and terns. David Cabot and Michael Viney once caught a Leach's petrel there - a scarce breeding species in this country and one whose favourite haunt is the Stags of Broadhaven. Duvillaun is also home to wintering barnacle geese, but not to the some extent as her neighbour, Inishkea, where as many as 2,600 have been recorded - well over 50% of the Irish total. They have been studied for almost 40 years by David Cabot, who has a little cottage on Inishkea South and spends time there. The geese arrive from their breeding grounds in Greenland in October and return there again in April. They like to graze on the short grass of the islands. The

grey seals pup in lnishkea in the Autumn. Inishglora because it is low-lying and takes the brunt of the Atlantic gales, is less popular with the birds, although storm petrels breed there, under the rocks and in the old ruins. In contrast, the sheltered island of lnishderry in Broadhaven is host to flocks of black-headed gulls and terns - sandwich, arctic and little.28

grey seals pup in lnishkea in the Autumn. Inishglora because it is low-lying and takes the brunt of the Atlantic gales, is less popular with the birds, although storm petrels breed there, under the rocks and in the old ruins. In contrast, the sheltered island of lnishderry in Broadhaven is host to flocks of black-headed gulls and terns - sandwich, arctic and little.28

There has been some talk recently of "developing'' Inishkea for tourism. ls that what the people of the Mullet really want? Our islands and their monuments are a very precious part of our heritage. Let us cherish them. In the words of Ruskin :-

"We have no right whatever to touch them - they are not ours. They belong partly to those who built them - partly to all the generations of mankind who are to follow us. The dead still have their right in them ''

Early Christians

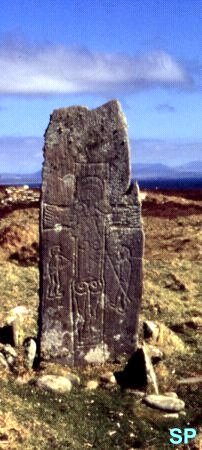

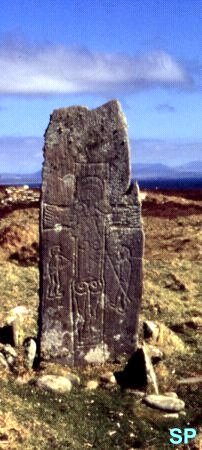

Duvillaun island, a short distance from Falmore, has monastic remains which date from the same period as Falmore and Inishkea. There is a Gallerus type oratory, a tomb of large slabs, with a crucifixion etched on the slab at the head of the tomb and a few beehive huts. The local people associate no known saint with it, simply calling the tomb, "Uaigh na Naoimh'' (tomb of the saint). 9

Permission to reproduce - thanks to Rita Nolan