| Bird | Number |

| Gannet - More | 2,050 pairs |

| Cormorant | 273 pairs |

| Shag | 265 pairs |

| Fulmar | 525 pairs |

| Kittiwake | 2,125 pairs |

| Guillemot | 21,436 individuals |

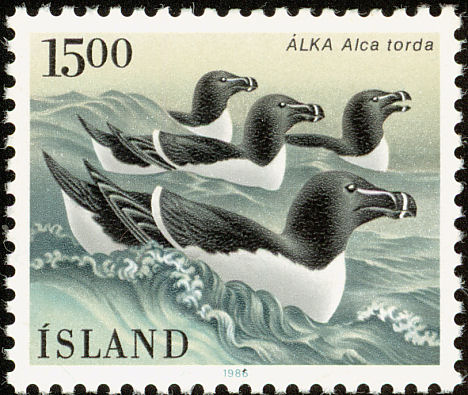

| Razorbill | c.4,000 individuals |

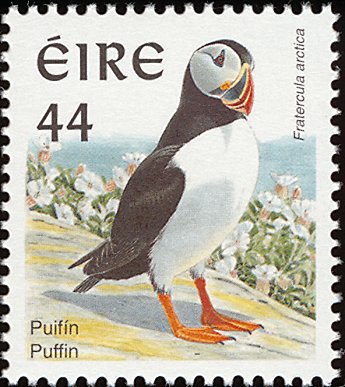

| Puffin - More | 1,822 individuals |

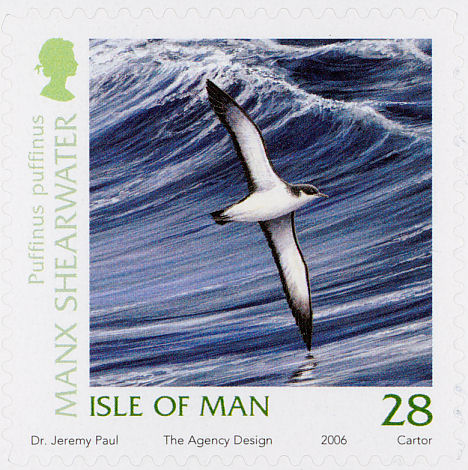

| Manx Shearwater | c.150-175 pairs |

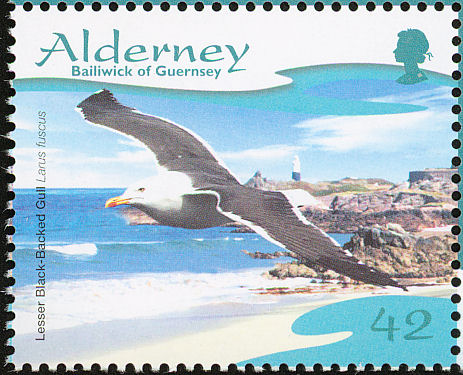

| Lesser Black-backed Gull | 245 pairs |

| Herring Gull | c. 50 pairs |

| Great Black-backed Gull | c. 90 |

| Peregrine Falcon | 1-2 pairs |

| Chough | 1 pair |

| Source: NPWS website which in addition to the above says "Great Saltee is a major site for spring and autumn landbird migration. Very large numbers of pipits, Swallows and martins, thrushes, warblers and finches occur, while smaller numbers of a great variety of other species (some very rare in Ireland) are also recorded." | |

The Saltee Islands lie three miles off the south coast, and at dead low water an arched deposit of rocks connects the smaller of the two islands to the mainland. Legend has it that St. Patrick pelted the fleeing devil with the rocks as he tried to escape the wrath of the holy man. Another legend tells of how Patrick borrowed a boat so as to visit the islands. A few hundred yards from shore the boat began to sink and the saint had to swim back. Angry and wet, St. Patrick cursed the sinking boat and turned it into a granite boulder that sits in the tidal stream to this day. The frustrated saint then built the causeway that l could see as a dark shadow gracefully bending out toward the closest island. Geologists characterize the formation of the gravel bar as a glacial deposit. As I floated across the causeway, bits of seaweed tumbled and raced over the bottom. I liked the sound of the legend better than the cold facts of geology.

The Irish love to tell a tale, and if in the telling the story gets a bit grander with each recital, then it only makes for keener listening on a windy wet night beside a turf fire. 'Throughout Ireland there are legends such as the one about the Saltee Islands. Whether the legend is believed or not, it is still passed on. In a land of superstition it is easy to see how the tales would be repeated as they had been for the last five or six hundred years rather than risk the possibility of a curse for questioning their origin or truth. Who would question a legend connected with the patron saint of Ireland? Certainly not any man taking to the sea in a frail, tar-covered boat. Or perhaps even a tippy yellow kayak. When I hear the telling of a tale or legend, l never ask if the storyteller believes his or her story. l am not overly superstitious, but I like the idea of a world that straddles the gray area of fact and myth. In truth, I want to believe there is more to some of the myths and tales than merely age-old superstition. I landed in Kilmore Quay for food and water before heading out for an overnight stay on Great Saltee, the bigger of the two islands. As I finished loading the last of the food on board, a middle-aged fellow walked over and watched me snap the black rubber hatches in place, then carefully double-check the seal on each one. With his hands jammed deep in his baggy trousers and his irish cap set back on the crown of his head, he said,

"She's a fine-looking boat, that one''

"Thank you. She's a fine boat, all right. Good in the rough water and fast enough when l need to cover some ground.''

"You'd be headin' over to the islands, then, are ye?''

"Yeah, I thought I'd go over and check out the gannet colony on the big island. l want to take some pictures and if it's okay I'd like to camp overnight.''

''Oh sure and why wouldn't it be okay? Ye can camp sure enough and no one will be bothering ye about it. There's a wee small beach on this side of the island that ye can see from here on a good day. Ye can pull the little lady right clear of high water and have a good look around. Ah, there's so many birds, ye won't be knowin' where to tum for a good picture."

The fellow's response to camping on the island was typical of the reception I had found along the way. There was always the initial curiosity, followed by advice on the weather, the seas, or maybe where I could get fresh supplies. As the afternoon sun reflected off the boat ramp and soaked into the stiff muscles of my back, I felt the ease of being a traveler in a friendly land. I never asked this fellow his name and he didn't ask me mine. It was enough to pass a few moments of the day, share a few thoughts, then bid each other a cheerful farewell. Before he walked up the ramp and out of sight, he told me he was a crew member of the RNLI, the Royal National Lifeboat Institute, and that he would keep an eye out for me on their training run later that afternoon. As he walked away, he paused, then said, "All the very best to ye, lad.''

One of the challenges of sea kayaking is that every time the paddler snaps the spray deck in place and pushes off from shore, he or she is instantly in an environment that is potentially dangerous. Wind, tidal currents, reflecting waves, and water that is cold enough to lower the core temperature and kill by hypothermia are factors of the sea. On a calm day with flat water and sunshine, the smooth glide of the boat can lull a paddler into complacency and the warning signs of the surrounding environment can go unnoticed. A line of clouds on the horizon, a shift of wind from one quarter to the next, or whitecaps a mile offshore where an hour earlier there had been none, all paint a picture of the constant interplay of sea and sky. The freedom and ease of paddling on calm days can quickly become a battle of nerves and stamina when these signs are ignored or misinterpreted. It isn't the sea that takes lives and brings grief to stormbound families, it is the careless drift of the mind that accepts the moment of calm without looking beyond for what surely will be a change. The kayak allows the freedom of travel, but it also demands that the paddler be ob- servant and have both skill and judgment to deal with the realities of the sea.

The three-mile paddle out to Great Saltee Island was not a long crossing. But it was one that l weighed with the same care as a fifteen or twenty- mile crossing. The forecast was for increasing winds, gale force, forty miles per hour, by late afternoon. Banks of high clouds were building in the southwest and the wind was just strong enough to begin forming small breakers halfway to Little Saltee. Without the effect of a current against the wind, whitecaps will start to build at fifteen mph. It is a rough estimate that l use when contemplating a crossing. The paddle to Great Saltee would take less than an hour, but that didn't mean it wasn't without risk. The tide was running half strength when I left Kilmore Quay. lf l tried to shoot straight across, it would carry me beyond the west end of the island. l would have to head east of Little Saltee and let the current wash me into its lee. From there, l could cut across the "sound'' between the two islands and deal with the steep, choppy seas that were funneled through the narrow opening. The lifeboat crew member had told me the channel had a bad reputation, as though it were temperamental and if provoked would stir up trouble. Local advice like that was something to listen to. The two mile crossing to the first island (Little Saltee) and the supposed rough water in the channel gave the landing on Great Saltee a different meaning: it wasn't only a destination but also a refuge if the wind and waves became too strong.

The low islands sat out on the edge of the immediate horizon: rounded humps of green, long and tapered as if drawn lower on one end by the tides that swept past them. From the mainland there was little detail other than shadow and sunlight drifting with the passage of clouds. As I drew closer, the base of rock that the islands sat upon rose out of the waves and took on the cracks and depth of ledges split in tumbled argles. Halfway to Little Saltee, the wind began to freshen and the waves curled over in white. By the time I had paddled into the lee of that island, the winds had increased to Force 4, twenty mites an hour. The waves were funneling through the passage of the two islands at a fast clip, tripping over each other as the wind rushed against the tide. I reached behind the cockpit for the nylon belt attached to the rear grab loop of the boat. I snapped the buckle around my waist and gave it a good tug. It was unlikely that I would get knocked over by the four-and five-footers, and just as unlikely that I would miss my roll and wind up swimming. But . . . I wanted to be prepared. These were conditions that I called my "double-tethered days'': the paddle tethered to my wrist with a short piece of webbing, and me tied to the boat with the black nylon ribbon running aft.

The waves in the middle of the sound rose ewer my head and completely blocked out the view of Great Saltee a half mile away. The clouds had moved in from the west, and the seas no longer sparkled with the morning's sun. Now they were black faces with tops of breaking white that poured through the channel and occasionally buried the stem of the boat with a noisy shove to one side. A series of breaking waves lay between me and the relative calm in the shelter of Great Saltee. The RNLI boat was half- way out from Kilmore Quay, its bow splitting the waves in twin arcs of white that the winds carried away. I thought how impossible it would be for them or anyone else to spot me in the rough water. Another wave poured over the foredeck and washed my camera over the side. I reached for the tether strap and hauled the waterproof camera back on board. If anyone could have seen me, the situation would probably look pretty hopeless: a strange-looking sliver of a boat being buried and tossed around like a cork on the sea. The difference was perspective. I had trained in waters rougher than these and knew what my abilities were. I was comfortable, alert, and enjoying the feel of the boat recovering from each rumbling wave and climbing up on the face of the next. The seas were big enough to test my skills but not so wild as to be threatening. They were perfect conditions for my first crossing of the trip. This was why I had come to Ireland; for the energy of open ocean paddling, to be washed by the salt spray and feel the boat driving toward an island filled with the mysteries of past ages. It was wild and romantic. A ten-year-old dream coming to life.

I had found a guidebook about the islands when I was in the small grocery store in town. As my bill for food was being totaled, I flipped through it and learned a little of the history of the islands. They had been inhabited since the Neolithic period, 3000-2500 B.C. The islands offered protection from bears, wolves, and wild boars, as well as other humans. There were plenty of fish, wild rabbits, and seabirds for food as well. Aerial photographs showed several large stone circles and what the archeological thought was an iron Age ring fort overlooking one end of the island. There is also a carved Ogham Stone in the county museum which originally came from the island. like so many other things in Ireland, the origin of the stone was uncertain but similar stones date from the early Christian period A.D. 400-800, and usually marked the burial place of a chieftain or scribe. Stories of medieval abbeys, Viking raids, and pirates using the islands' sea caves to hide their loot became jumbled in my mind as I tried to compre- hend five thousand years of history.

I paddled into the lee of the bigger island, landed, and slid the boat over a roll of storm-tossed kelp. A footpath cut through the thick barrier of head-high brush and briars above the beach. I left the Little Lady resting on the kelp above high water, stepped through the opening, and followed the mazelike path. Ruins of stone outbuildings seemed to be everywhere. Their crumbled walls were draped with vines, and tight clusters of grass grew in the empty spaces where mortar had long ago fallen out. A faint trail split from the main path and led to a single-roomed cottage surrounded by a tangle of underbrush. The half-opened door hung on one high rusty hinge. It felt spooky and friendly at the same time. The perfect place, I thought, for a gnome to live. Beneath the eaves and built into the corner of the foundation was a stone-lined well. A grotto of moss-softened stone with two steps led down to its dampness. A spider's web hung from the curved sides of the well, fine beads of dew clinging to the threads carefully woven across the arch. And overhead a domed ceiling of fitted stone. Tiny insects skated across the still pool. I cupped my hand and lifted a palm of pure cold water to my lips.

I returned to the main track and followed its curves toward a stone farmhouse, my head filled with the excitement of the sound crossing, the history of the island and the discovery of the well. Suddenly, a short, gray- bearded fellow dressed in frumpy clothes appeared around the bend. I almost jumped off the trail in fright. He was certainly too big to be a gnome and just as startled to see me as I was to see him.

After our mutual shock, we introduced ourselves. Oscar Merne worked for the Irish National Park Service. He was on the island with another ornithologist monitoring the various seabird colonies that nested on the cliffs. He told me where I could find the gannet, razorbill, and puffin colonies, and encouraged me to have a look around. Few people come out to the island and the birds are very tolerant of careful observation! The footpath cut across the low rise of the island, disappearing amid purple heather stunted and sculpted by the winds. Tiny flowers grew in the protection of the heather, contrasting yellow against soft purple, while a thickening mist watered the island contours with drops that clung to the ferns, heather, and grass. A strong ocean wind carried the sound of crashing waves as I followed the winding trail to the cliff edge. Across the waves, black specks appeared out of the mist and flew hell-bent for the cliffs below me. Eye-watering winds tore past as I carefully made my way to the grassy lip; one foot forward, one back as I gazed down at the roiling seas below. Clear blue waves wrapped around pinnacles of rock, then rolled in and hit the island in a barrage of rumbling white water. Just beyond the reach of the flying spray were hundreds of razorbills and guillemots standing on ledges streaked with guano. They stood shoulder to shoulder, looking out to sea and shuffling to find better footing as the wind ripped past the cliff face. More birds appeared out of the mist, flew at wave height, then climbed suddenly and with a flare of wings somehow found a foothold on the crowded ledges. Neighbors moved over, craning their necks to look down at the waves or up to the clifftop. Several others chose to launch into the winds and soar away, or drop into waves below and disappear beneath the surface in search of food. Cormorants, shags, fulmars, kittiwakes, and huge black-backed gulls were everywhere. Fifty feet of bird-filled air separated me from the waves below. Outstretched wings swept by in a blur as I tried to identify the individuals flying past. A curious fulmar flew in close, then circled back into the wind and hovered motionless twenty feet away, its crystal black eyes set so elegantly within a snowy white head.

In a hushed voice that came from a place deep within, I said: "You are so beautiful, my friend. What have you seen and where have you been today?''

Gusts of wind lifted and buffeted the fulmar as it struggled to hold its position. Thirty or forty seconds passed, each of us studying the other, until with a dip of a wing the fulmar tore away. I pulled the fleece collar tighter around my neck, zipped into the hood of my raincoat, and continued along the cliff. The trail cut through tangles of wildflowers and grass, and at each point where it met the cliff edge, I could look down on rockfalls crowded with hundreds of seabirds.

Oscar had told me the main gannet colony nested on the southern, most exposed tip of the island. The trail dropped into a shallow ravine, then climbed back into the noise of the wind. Across a chasm filled with raging broken waves was a jumble of blocks and ledges that climbed a hundred feet out of the sea. There wasn't a single blade of grass or vegetation on the small mountain of rock and every square foot of space was covered with nesting gannets. The guidebook said there were one thousand five hundred pairs of these golden-faced birds with seven-foot wingspans, but I had no way of understanding that number until I had crested that last rise and saw the colony.

I leaned into the powerful gusts and crept from one rock to the next until I was at the edge of the chasm. A flat-sided boulder offered some protection from the blasts of wind. Twenty feet to the left and slightly below me was a subcolony of two hundred gannets that ignored me as I sat huddled against the rain-splattered rock. On every ledge or flat rock was a nest: seaweed, bits of rope, discarded feathers and an adult gannet protecting its domain with stabs of its beak. On the crowded nesting rocks there was a constant testing of boundaries as individuals reached cautiously for a stray piece of seaweed or pulled a piece of orange netting from a neighbor's nest. Half-grown chicks with black heads would appear from under their parents. The young birds grew fast on a steady diet of fish and they looked like teenagers literally afraid to leave the nest. After a quick look, the chick would retreat under the warmth of folded wings and the arent would attempt to cover the young bird again.

Gannets returning from fishing or carrying nesting materials would suddenly appear from below the cliff in front of me. 'They would bank into the wind, break their forty-mile-an-hour airspeed with cupped wings and flared tail feathers, then somehow find their mate amid all of the upturned bills. From where I sat, I could see the fine overlapping feathers on the gannets' breasts and the long flight feathers of their wings rippled by the wind. A second or two of stalled air time and each big bird would settle down on the nest and join in a gentle duel of beaks with its mate. Again and again the pattern repeated itself throughout the colony, while all around the space between cliff and sea was filled with every species of bird on the island tearing along on the winds.

For the moment, my life consisted of only what was immediately in front of me-a world of screaming winds, flaring wings a dozen feet away, and the marvel of so much life and energy. Another fulmar soared up the face of the cliff and purposefully stalled right in front of my perch. That brilliant crystal eye stared into mine as if it could read my thoughts. I could feel the wind buffeting its body and passing beneath the short, rounded wings as if I was part of the flight. A puffin came in for a controlled crash landing onto a rocky ledge. Once safe on land, it tucked its wings and waddled into a sheltered comer of rock to stand at attention and look out over the cliff

As I sat there I was aware of how still I had become, and how insignificant I was compared to everything around me. The air was filled with the noise of the wind, the waves washing powerfully against the rocks below, and the helter-skelter flight of seabirds whipping past on the gusts. I was surrounded by all this energy and activity, yet inside there was only silence, an overwhelming sense of awe.

As the sky threatened heavier rain, I stretched my cramped legs out of a crouched position and slowly moved away from the colony. I followed the path along the sheltered side of the island back to the farmhouse and the beach, where my boat sat waiting. Darkness had settled in as I pulled my sleeping bag and thermarest from the front compartment and followed the trail back to the overgrown cottage. Inside, a rickety ladder led from the damp stone of the main floor to a low-roofed loft above. In the dark I spread the sleeping bag on the wooden floor and listened to the rush of wind battering the cottage. My body was tired but my mind was filled with memories of the day and imaginings of what was ahead. In the morning I would head back to the mainland on a ten-mile diagonal crossing to Hook Head, then on toward the west coast. The gale-force winds that had been forecast howled against the stone cottage and whirled around dreams of seabirds, rocks, and waves.